HA note: The following is reprinted with permission from Heather Doney’s blog Becoming Worldly. It was originally published on July 7, 2013.

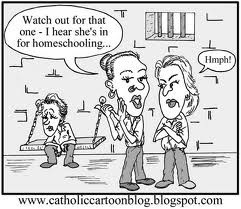

I googled “homeschool” to see what pictures came up. Many of them had to do with socialization and the messages that homeschool parents get and give about it. So I figured I’d talk about homeschooling and the issue of socialization today and use some of the cartoons I found in the process. Some of them are a little disconcerting in the way they point out issues I see, just maybe not quite in the ways the cartoonists intended.

What is This “Socialization Problem” You Speak Of?

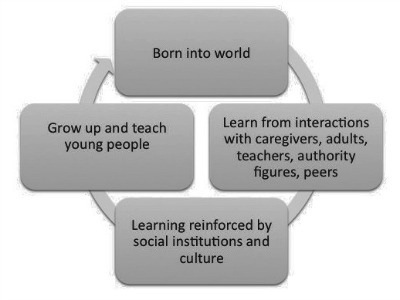

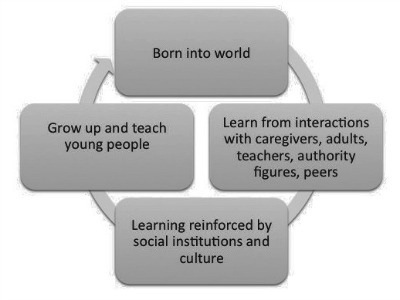

So first a bit about what socialization is and how it relates to homeschooling. This diagram explains socialization pretty simply and it comes from a site that talks abut stopping cycles of discrimination that are often passed on intergenerationally.

I think the site the diagram comes from – Parenting for Social Change – makes an excellent point – that this is generally how socialization is done but socialization can sometimes be bad. You can absolutely be taught harmful things as well as positive things in the course of your socialization and most people are taught a mix. What homeschooling parents often become inclined to do though is try to eliminate or greatly reduce these “bad” things by winnowing their child’s socialization opportunities down to only parentally vetted and approved sources and quite often those approved sources are fellow homeschoolers, religious leaders, highly edited texts and media, other “likeminded families,” and sometimes, when the parent is particularly controlling or inept at socialization themselves, nobody at all except for the immediate family.

Yes, this last one is a real big problem because terrible things can happen when families get isolated like that and it is a big risk factor for all kinds of abuse, neglect, and poor mental and physical health. Thing is, this social isolation problem happens in homeschooling much more frequently than it should. In fact, even in Brian Ray’s wacky (and so methodologically unsound that I am stopping myself from going on a rant about how many problems it has) “Strengths of Their Own” study included something I found interesting about it. See if you can catch it.

That’s right. The third bar from the bottom. The yellow one. If 87% of the children in Brian Ray’s highly self-selective study play with “people outside the family” (and I will leave you to ponder right along with me as to why this wording is not “other children outside the family”) then that means that 13% of children in Brian Ray’s study do not play with others outside of their own family, which I would most definitely define as a socialization problem. If Brian Ray, excellent fudger, misconstruer, self-quoter, and ideological spit-shiner of homeschool data extraordinaire, has almost 15% of the kids in his rather cherry-picked study having this issue, how common must it actually be in real life and how do people in homeschooling react to this issue? Well, let’s see…

Socialization Sarcasm

This cartoon makes fun of the concept that socialization problems exist in homeschooling. To me it implies that socialization happens so naturally that it simply isn’t something a homeschool Mom could forget. Why? Well, I’m honestly not exactly sure. Socialization is a component that definitely can be ignored or accidentally left out and it has openly (and wrongly) been discounted as being unimportant by many prominent homeschool leaders. Because it has been ignored and dismissed as a necessary part of many homeschool curriculums is the main reason why homeschoolers have gotten the reputation for being unsocialized in the first place.

Most homeschool kids don’t like being stereotyped as unsocialized or feeling like they are unsocialized (I mean really, who would?). So there’s also some memes and jokes that have been spread by teenage homeschoolers implying how inherently dumb or inappropriate they think it is when people make socialization an issue. Most of these involve poking fun at the “myth” that socialization is a problem in homeschooling. There is this YouTube video by a homeschooled girl who is trying to do this by distinguishing “the homeschooled” from “the homeschoolers” and while I find it funny, I’m quite sure that her pie chart is wrong and she perpetuates elitist stereotypes she has likely heard throughout her homeschooling experience.

This blog had a post by a homeschool graduate complaining about people asking what’s become known as the “socialization question” and in her post she uses a picture I’ve seen fairly often. There’s even t-shirts with this printed on them that you can buy.

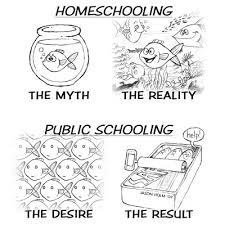

Socialization is Fishy

So what do homeschooling parents think about the socialization issue when theydo actually address it? Let’s start out with this cartoon, as it’s used a lot. It claims that a lack of socialization in homeschooling isn’t just a rare problem, but an outright myth. It implies that homeschool kids are not only actually in diverse environments as part of a natural ecosystem but are thrilled about it. It also implies that children who are socialized in public school are like half-dead sardines in a can rather than the school of likeminded fish they are expected to be.

This cartoon is a direct dismissal of there being any merit to the “socialization problem” and it is compounded with a public school counter-stereotype. This is unsurprising to me as the argument that homeschool socialization problems are an outright myth is quite often included with something disparaging about public school or insulting to teachers (and this cartoon is no exception). Notwithstanding how insulting it is to imply that most people who go through public school are like dead fish, is this depiction of homeschool versus public school in any way accurate? Well, I imagine for the occasional situation it is, but in general, certainly not.

Oddly this cartoon was actually almost the exact opposite of my experience. In the CHEF homeschoolers group I was in it was all white Christian families and our parents had to sign a statement of faith to join. It was absolutely a school of fish all swimming the same way and because we got together infrequently, I generally felt like that fish in the fishbowl. Also, when I went to public school in 9th grade I was certainly no canned sardine, even if I wasn’t exactly the manic fish thrilled at the ecosystem in the upper righthand corner. The teachers often tried to corral us into all doing things the same way but we didn’t make it altogether easy for them and generally I expect it was a bit like herding cats. We were all individuals, as were the teachers. I had favorite teachers and subjects and ones I didn’t like and I made friends of different races and beliefs and political persuasions, many of whom who are still my friends and acquaintances to this day.

The Dark Knowledge of Teen Degenerates

Here’s another cartoon about homeschool kid socialization from a slightly different angle, and this one does address the idea that kids don’t always do what you want them to do and by invoking the dreaded “peer pressure,” implies that its all bad. Which one is it – are they lobotomized sardines in a can or are they violent and rebellious ingrates? Make up your mind! Also, how realistic is this, do homeschool moms actually think public school kids are like this? Where are the public school kids who are not “at-risk” of being part of the school to prison pipeline? Why aren’t there any of those at the bus stop?

Also, in this little dystopian cartoon, gang members with knives read books on values (morally relativistic ones, no doubt), evolution, meditation, and “new age” religion (if that isn’t a culture wars, fearmongering buzzword, I don’t know what is) and pregnant girls read about sex ed and still don’t know what made them pregnant. This cartoon is crazy stuff. People don’t drink beer and shoot up heroin (yeah, there’s a needle on the ground in the cartoon) while waiting for the school bus (although some do smoke cigarettes). People who read a lot don’t typically join gangs. People who know about comprehensive sex ed aren’t any more likely to have sex than kids who don’t and they are much less likely to accidentally get knocked up. Honestly, if this is what anyone actually thinks the world is like then they are not fit to educate other human beings and they probably need some mental help themselves.

Sweet Homeschool Girl in the Ghetto

This cartoon is similar to the previous one in that it also indicates that public school socialization is all bad, but it depicts the expected reaction of the homeschool girl in the public school and implies that if your daughter goes to public high school (obviously radiating her feminine purity with a big hair bow and below-the-knee church skirt) that she will soon be shocked and horrified to encounter people dressed immodestly, young people openly dating, tattoos and piercings everywhere, vandalism and crime, blatant teenage rebellion, and big scary black boys that look more like grown men. So obviously the answer is to just have her at home not knowing that people who are different from her exist, and make most of the people her age out to be disgusting, immoral, and scary, right?

I followed this cartoon to its site, a blog called Heart of Wisdom, trying to get a higher resolution picture. The blog talked about how homeschool kids should only selectively socialize with other Christians and claims this is biblical. Yep, this is just the type of homeschooling “socialization” I am familiar with. It’s a form of social isolation and indoctrination called “sheltering.” This stuff is all about parental fear and desire for control and helicopter parenting to this extreme is very unhealthy for your child. It will mean that in adulthood that they won’t know how to function at an optimal level. You cannot shield your kid from all “bad influences” and indeed there is nothing in the bible that says your kids cannot play with the kids of people who have different beliefs. That is quite a stretch and it is insular, cultish thinking.

My Homeschool Kid is Smarter than Your Honors Student

That same Heart of Wisdom blog had this other cartoon about homeschooling, so I followed that link and it was to a page dedicated specifically to homeschool cartoons. When I see stuff like this cartoon I have to once again ask – is this supposed to be funny? Do these people actually think this is accurate? My main question, though, is why the elitism and negativity? Even if your kid is getting a much better education in homeschooling, why talk trash about children who through no fault of their own don’t have as good of an education? Why make it into a competition, act like homeschool kids in general are “better” than other kids? It shows me some immature and defensive parenting, really. If you revel in it when someone else isn’t doing as good as you it shows you are 1) being a jerk and 2) secretly worried that you’re no good at what you’re doing. Nobody should ever be excited about other kids having a sub-par education, thinking it makes them and their kids look better. That’s just gross.

As it is, I find that there is a grain of truth in this cartoon but perhaps not quite in the way the cartoonist intended. I’ve known a lot of homeschool kids who do use big words in conversations and they soon realize that it comes across as awkward when they socialize with other non-homeschool kids. Admission: I was that kid myself. I read a lot of classic literature and became familiar with words that simply aren’t used in everyday speech anymore. Trying to use them in peer-to-peer conversations didn’t reflect on me being smarter. It reflected on me not having a modern day frame of reference as to what is appropriate. It reflected on me being socially backwards. Lots of public school kids who are bookworms like I was know many big words. They also know the right words to use for their audience. Context is everything. An unsocialized homeschool kid doesn’t have that context and very well might find that using 18th century literary terms in a conversation about basketball will indeed get people looking at them sideways. If homeschool parents want to be proud of that, think it makes their kid (and by extension them) “better,” it shows they truly don’t understand the issue at hand.

Parental Fear & Social Anxiety

That’s where I think we hit the crux of this whole thing. I think the main issue is parental angst and fearfulness. Too many homeschooling parents socially struggled in school themselves and/or got into drugs or unhealthy sexual relationships. Instead of taking a broader view today, they expect that they need to hide their kid away from these settings or the exact same thing will happen to their kid even though their kid is in a different school district in a different generation and *gasp* a different person. These parents become scared of or hurt by the society we live in, withdraw, and then use homeschooling as an excuse to be separatist, snooty, and helicopter over their kids. These are not positive reasons for homeschooling and these are the exact kind of fearful and overbearing attitudes that lead to socialization problems for homeschool kids.

Because people with strong views often find themselves in positions of leadership, those with exclusionary, separatist, and elitist attitudes often end up running things and then set this negative and divisive tone for the homeschooling group and the community it serves. It’s so pervasive that even some “second choicers” who start homeschooling simply because the other educational options in the area aren’t up to meeting their child’s particular needs (which is an excellent reason to homeschool, in my opinion), can get sucked into this culture, an “us versus them” mindset where homeschooling represents everything that is pure and good and healthy for children and public school and the people and structures that support it represents everything bad. This creates a parallel society of sorts and then you see people start calling public schools “government schools” in a pejorative sense. All this “us versus them” talk fans the fear that homeschooling parents are vulnerable (although still superior) outsiders who are or soon will be discriminated against and this in turn leads to easy exploitation of these scared people.

Why does widespread homeschool participation in things like the fundamentalist-led HSLDA, which capitalizes on these fears and requires dues money (that then goes into their cultish culture wars arsenal) for unnecessary “legal protection” exist? Because many these people are too freaked out to do anything more than cling onto a protector, ignoring all evidence that their “protector” just wants to use them – financially and for furthering a disturbingly anti-democratic agenda. This fear grows and leads to the kind of mindset that spawns ridiculous cartoons like the one below.

Put in prison for homeschooling – really? Of course in this cartoon there’s that same (expected) depiction of scary people with piercings, this time instead of a shocked daughter (projecting much?) it’s got a dejected homeschool Mom being shunned by hardened criminals who sarcastically note that her “crime” was homeschooling.

Homeschooling parents who follow these “leaders” (often starting because their local homeschool support group requires or recommends HSLDA membership) hear these divisive messages and become scared to death of being framed, exposed, persecuted, worrying that they will land in jail just for homeschooling. It may be a wacky and unrealistic fear given what’s actually going on, but if people hear it often enough they often come to believe it, along with the bogus stats and stories claiming that homeschooling is as close to perfect an educational option one can get in such a messed up society, and the myth that there is no evidence to the contrary because homeschooling is just so awesome.

Because homeschoolers test scores aren’t made public and often not even expected, registration isn’t even required in many states, and most people don’t pay much attention to homeschooling unless their kids are being homeschooled. Homeschool movement leaders have been able to get away with exhibiting the cream of the homeschooling crop as representative of all homeschoolers. This has painted an inaccurate picture and hurt the vulnerable kids by leaving them ignored as they fall through the cracks.

Saying “our homeschool kids are socialized but socialization doesn’t matter and in fact it generally sucks if it isn’t coming directly from parents” is a very unhealthy attitude to go into educating with. Responsible homeschooling parents really need to do a bit of soul-searching as to why they tolerate these inaccurate depictions of what socialization is and isn’t, why there is this the across-the-board maligning of all public schools within many homeschool communities, and why so many participate in this ugly (and frankly in my opinion undeserved) elitism, and contribute to such extreme (and inaccurate) stereotyping and putting down of children who have had to attend lower quality inner-city schools, all in order to inflate the merits of homeschooling.

Two big question:

(1) Does this kind of attitude help do anything beyond artificially boosting homeschool egos?

(2) Is there any need for this behavior if homeschooling is really so awesome?

Also, if there is no good data on the problems of homeschooling then instead of celebrating the cobwebs we need to be collecting more data. Every single education method in this world has problems and the places where the problems are denied is where child maltreatment can and does flourish.

The Truth Between “Stereotype” and “Myth”

I get the message that not all homeschoolers are cloistered and don’t know how to talk to people their own age, but the fact is that too many are and we need to recognize that it is a real problem affecting a sizable percentage of homeschool kids. Also, homeschoolers are simply not the most brilliant people in the world or inherently “smarter” than other kids, and as such they shouldn’t need to feel pressured to achieve perfection, perform as child prodigies, or that there’s a black mark on them if they mix up “asocial” and “anti-social” in a conversation.

This “myth of the unsocialized homeschooler” is an issue in homeschooling but the prevalent idea that the socialization problem is a myth is the real problem, not the legitimate questions and concerns about socialization that homeschool parents keep being asked. Those questions actually need to keep happening because social isolation and ostracism in any setting (including homeschooling) often follows a person into adulthood, and can leave people struggling with social anxiety, a small social network, low levels of social capital, mental health issues, and an unnecessary amount of sad and lonely memories.

The least we can do is stop making fun of people, stop being in denial, stop pointing fingers elsewhere, and acknowledge that it is real, it happens too often and it should be assessed and addressed as the serious problem that it is.